Dal postmortem di Cloudflare:

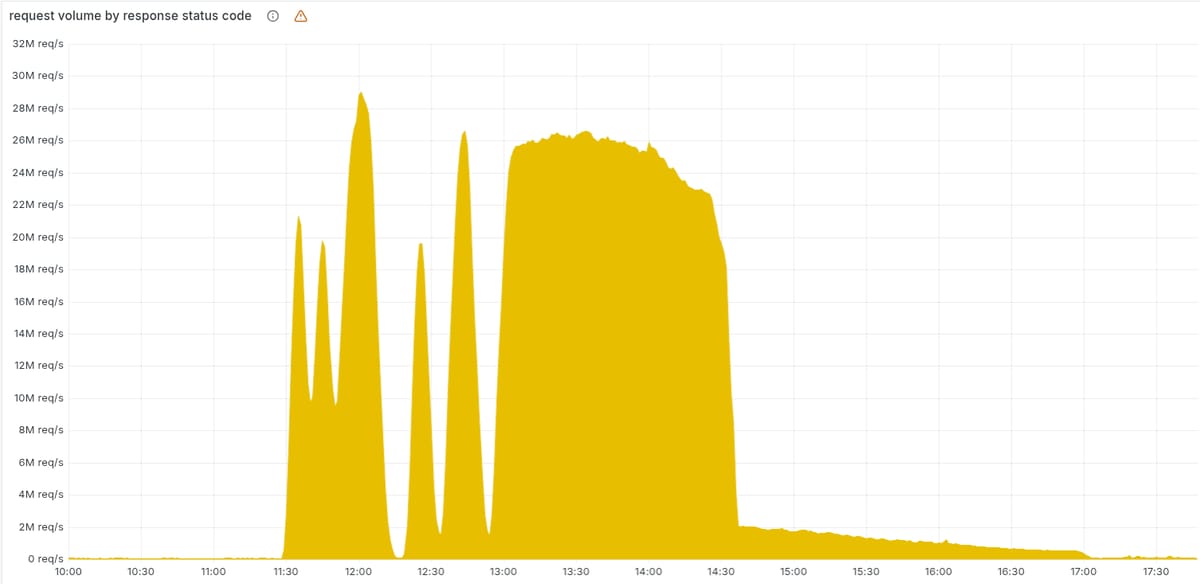

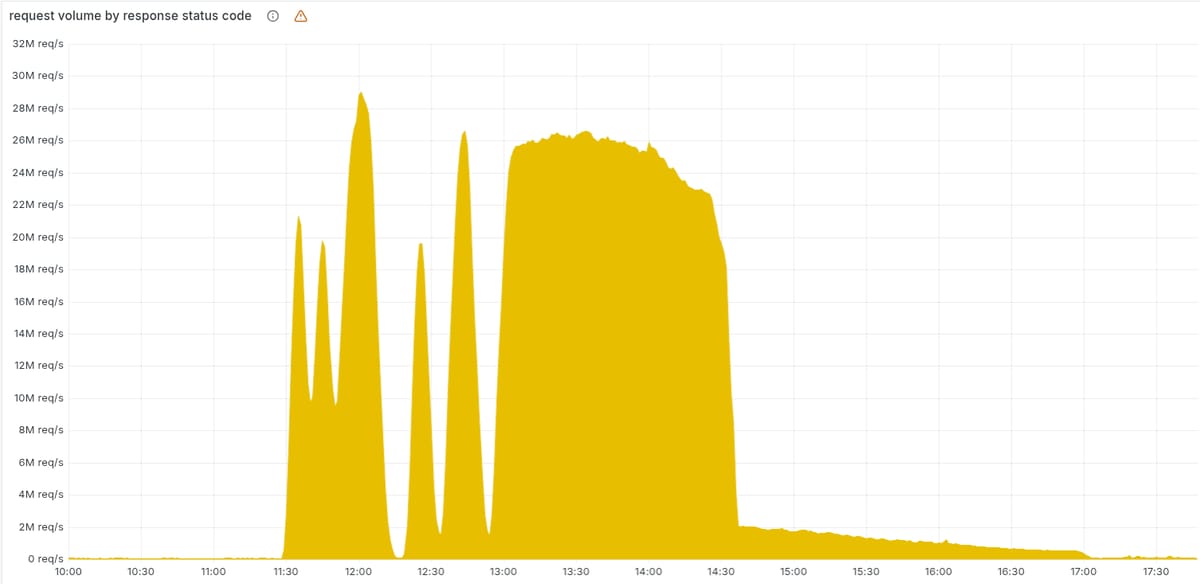

Il motivo delle fluttuazioni iniziali di errori 5xx è dovuto al deployment di un file di configurazione errato del "bot score" della Bot Protection:

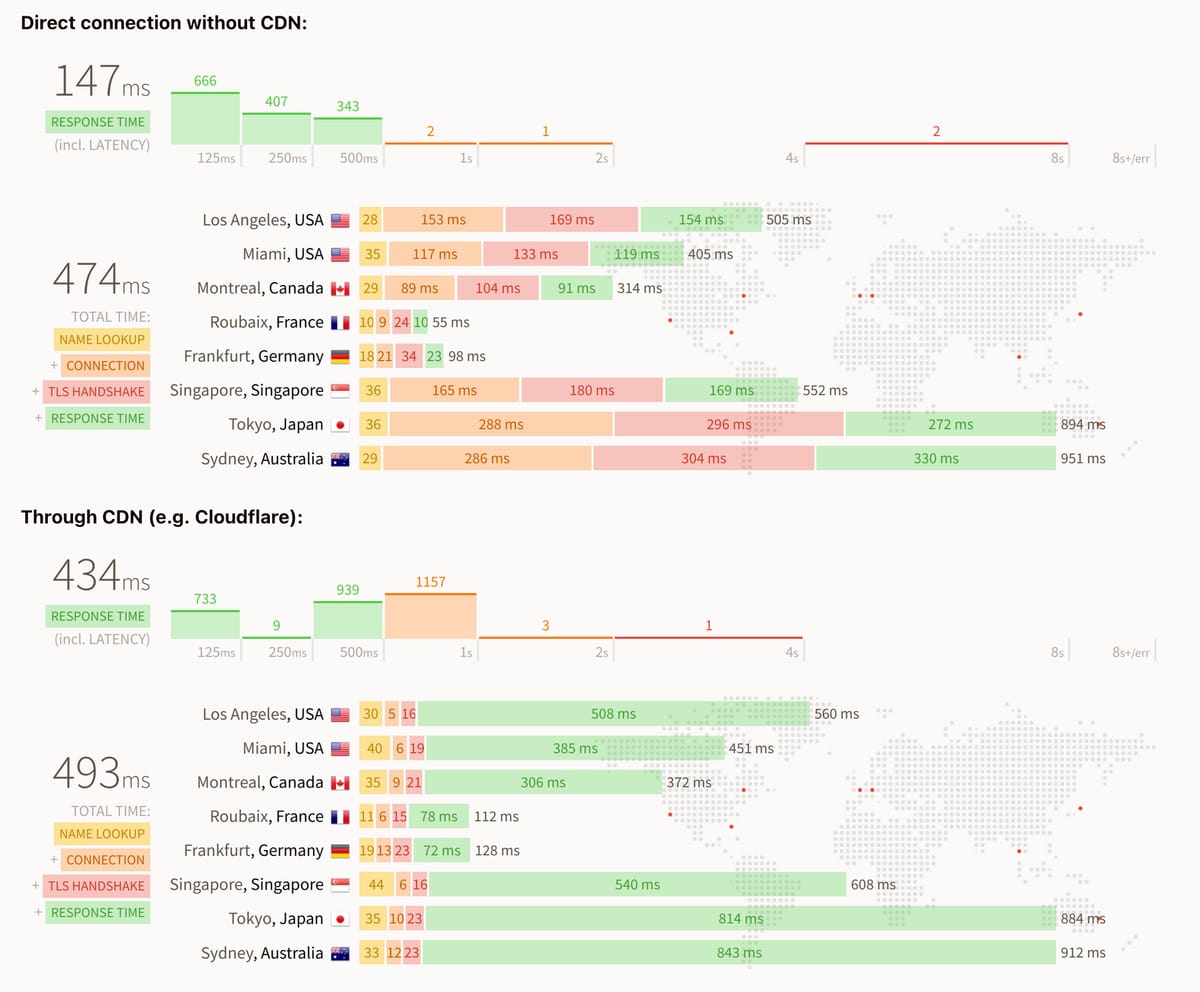

As a result, every five minutes there was a chance of either a good or a bad set of configuration files being generated and rapidly propagated across the network.

E infine veniva sempre deployato il file errato, globalmente e istantaneamente (la stessa causa di altri precedenti outage globali di Cloudflare):

The model takes as input a “feature” configuration file. A feature, in this context, is an individual trait used by the machine learning model to make a prediction about whether the request was automated or not. The feature configuration file is a collection of individual features.

This feature file is refreshed every few minutes and published to our entire network and allows us to react to variations in traffic flows across the Internet. It allows us to react to new types of bots and new bot attacks. So it’s critical that it is rolled out frequently and rapidly as bad actors change their tactics quickly.

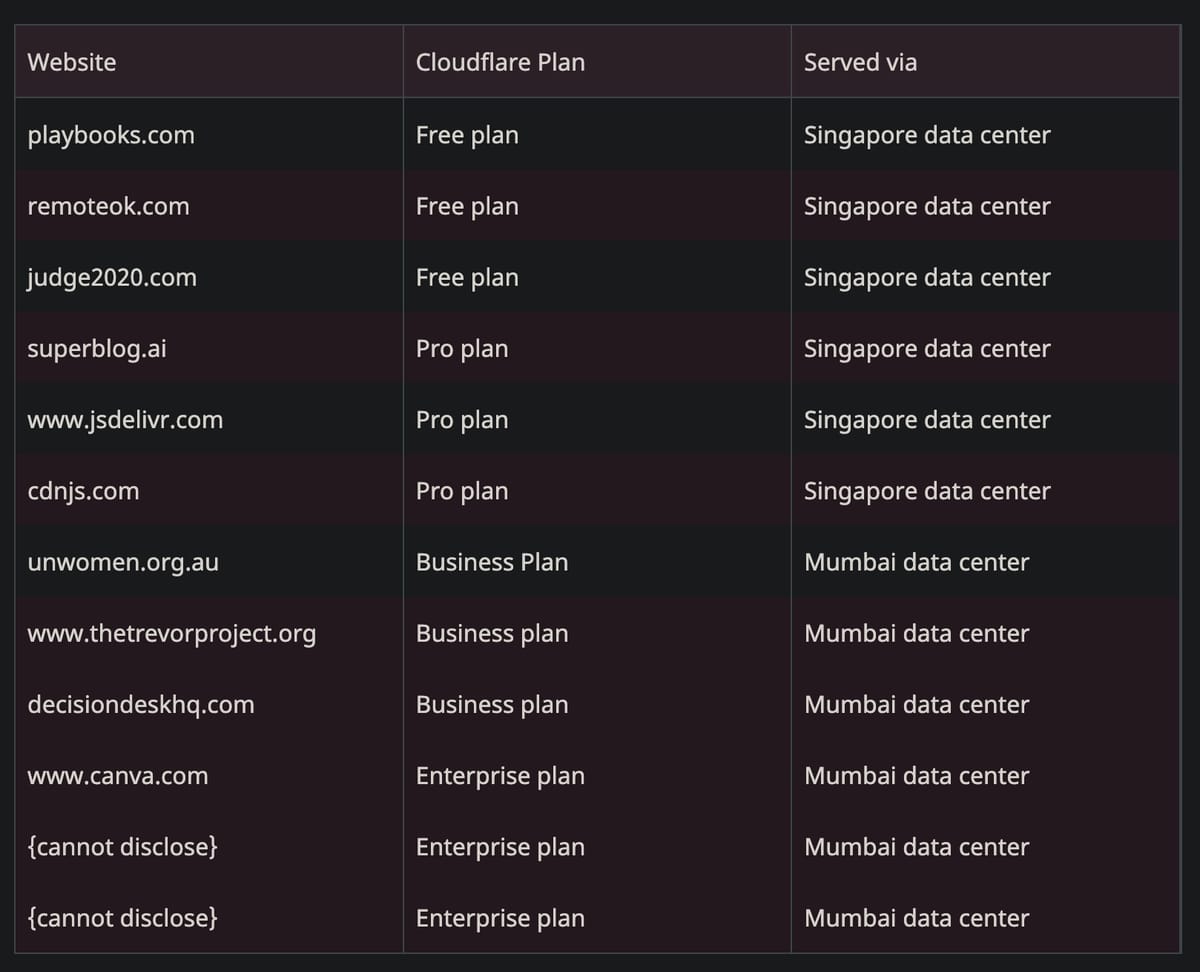

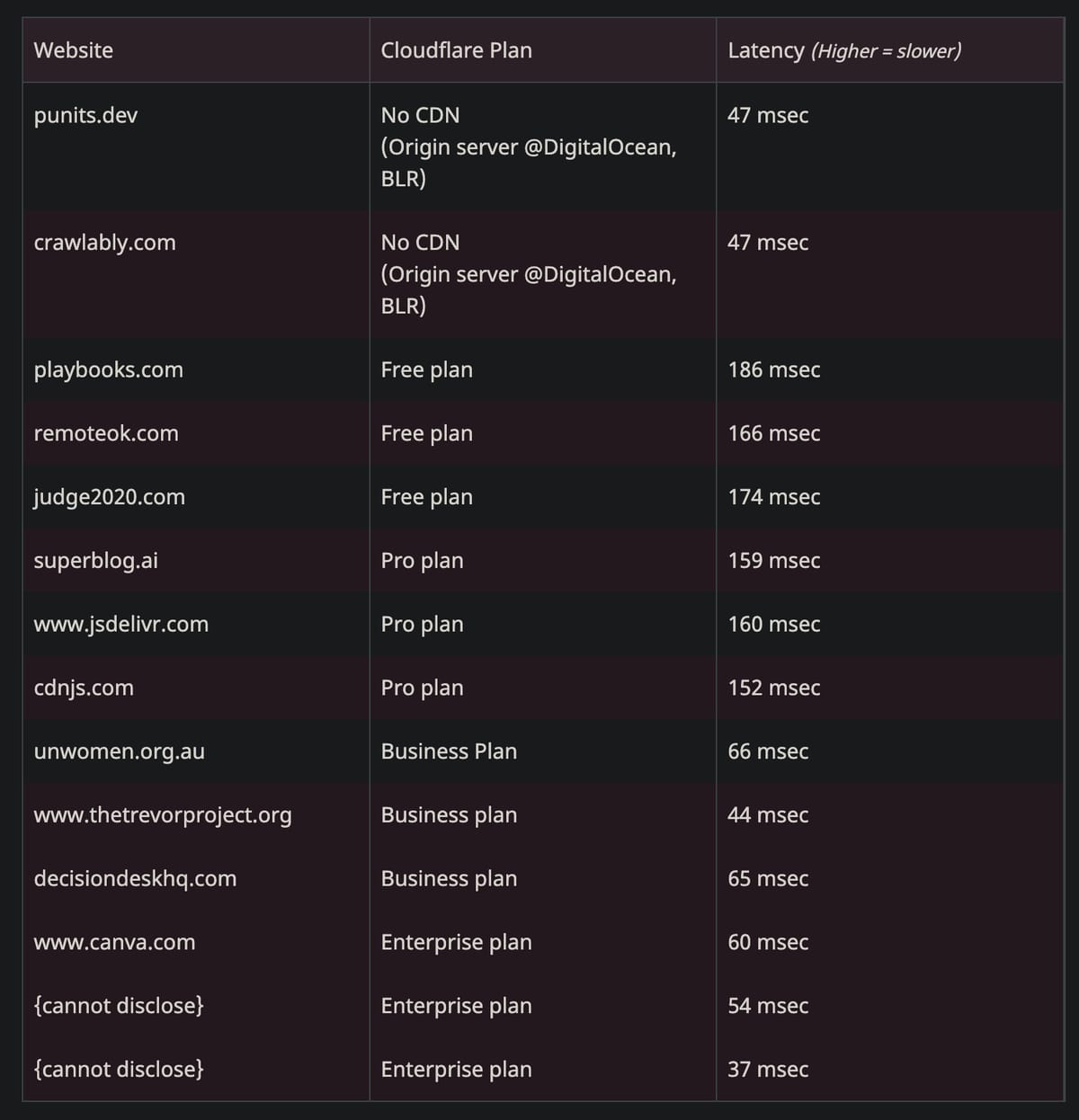

Il motivo per cui alcuni siti non erano affetti:

Customers deployed on the new FL2 proxy engine, observed HTTP 5xx errors. Customers on our old proxy engine, known as FL, did not see errors, but bot scores were not generated correctly, resulting in all traffic receiving a bot score of zero. Customers that had rules deployed to block bots would have seen large numbers of false positives.

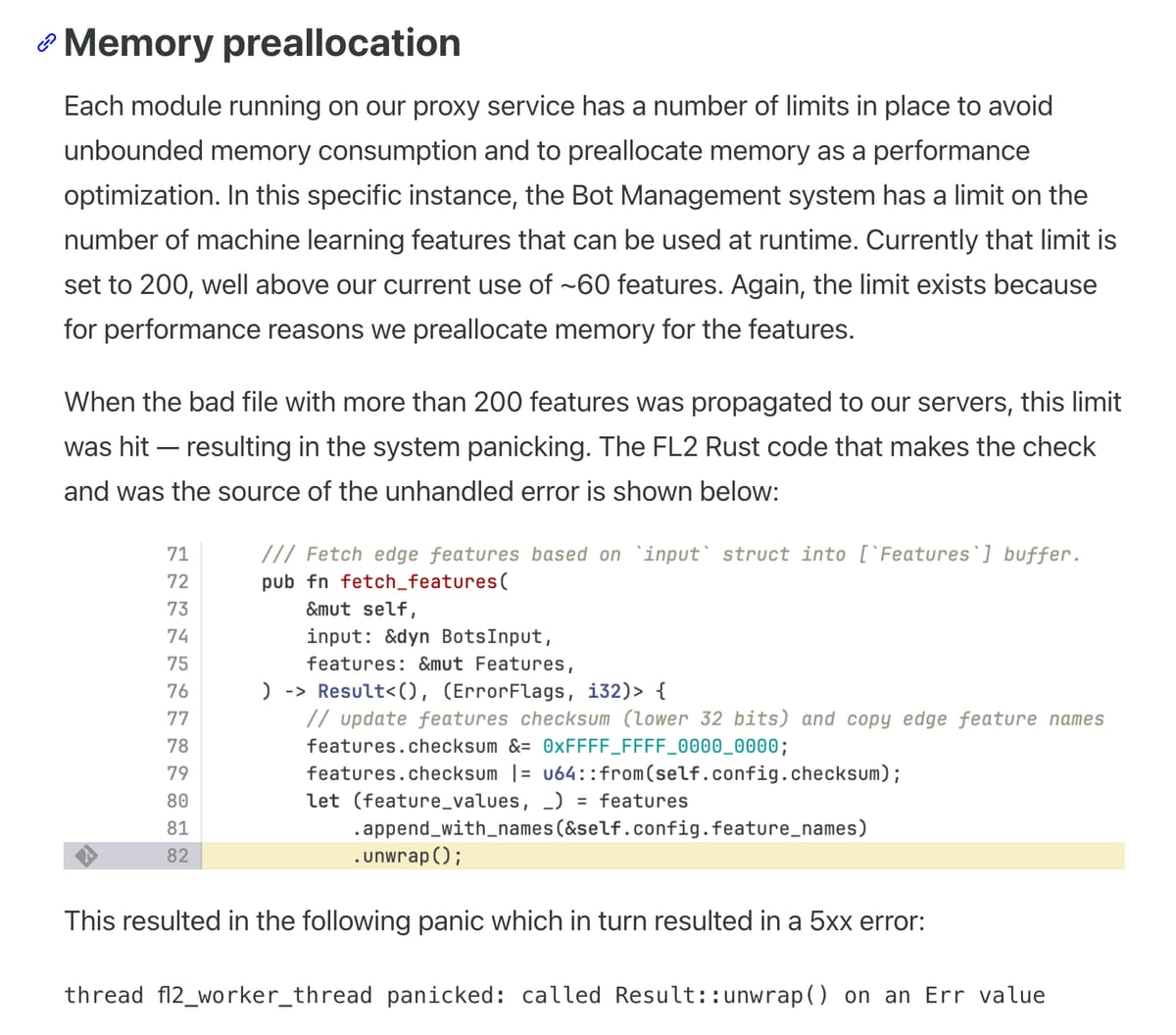

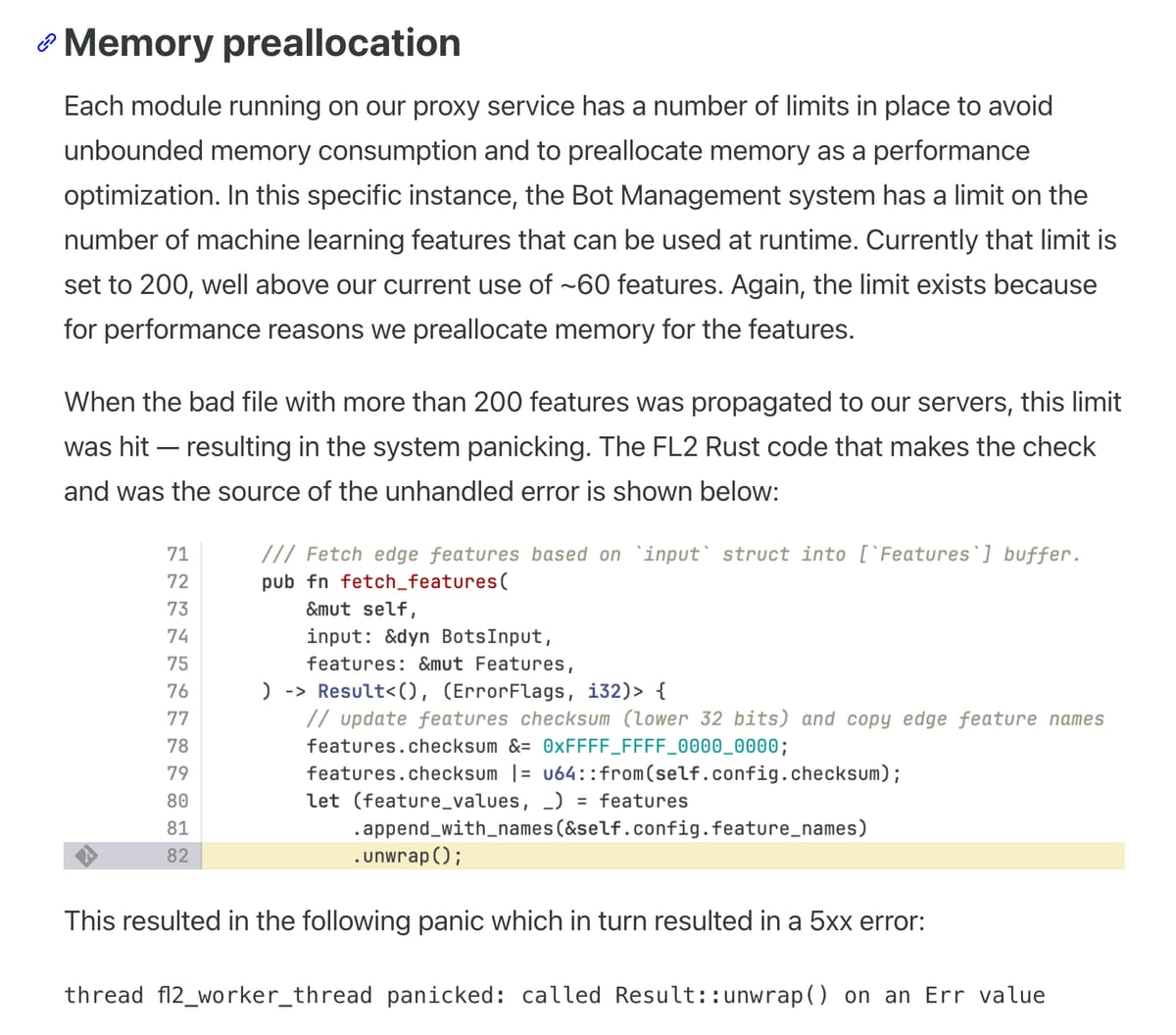

Il file di configurazione conteneva dei dati errati perché per via di un cambio di configurazione la query ClickHouse estraeva più dati del dovuto. Il proxy edge lanciava un'eccezione perché non si aspettava quella quantità di dati:

Cosa c'era quindi che non andava:

- La query era errata (ok, può capitare).

- Non c'era validazione dell'output della query (feature duplicate), che finiva quindi direttamente deployato globalmente, a quanto pare.

- Sull'edge c'era un limite fisso di 200 feature attese, ma non c'era nessuna validazione che il file ne avesse effettivamente di meno.

- Non c'era nemmeno "fail safe" nel caso in cui succedesse.

EDIT: su Hacker News osservazioni molto simili:

They failed on so many levels here.

How can you write the proxy without handling the config containing more than the maximum features limit you set yourself?

How can the database export query not have a limit set if there is a hard limit on number of features?

Why do they do non-critical changes in production before testing in a stage environment?

Why did they think this was a cyberattack and only after two hours realize it was the config file?

Why are they that afraid of a botnet? Does not leave me confident that they will handle the next Aisuru attack.